At the end of the 1920s, the attention of constructivist architects, in particular those of OSA, increasingly shifted toward a radical critique of the city itself, focusing on visions designed to overcome urban concentration, and introducing concepts of diffuse urbanisation, linear and green cities, ultimately theorising the concept of disurbanism. This term was basically the result of the controversy with the supporters of ‘urbanism’ (a Russian term that differs from the technical discipline that signifies urban concentration). In this vision, the total liberation of humanity from the chain of the past could not be accomplished without suppressing the antithesis between city and country. Maintaing the separation between urban and rural lifestyles would naturally lead to the reproduction of the inequalities and injustices of bourgeoise society.

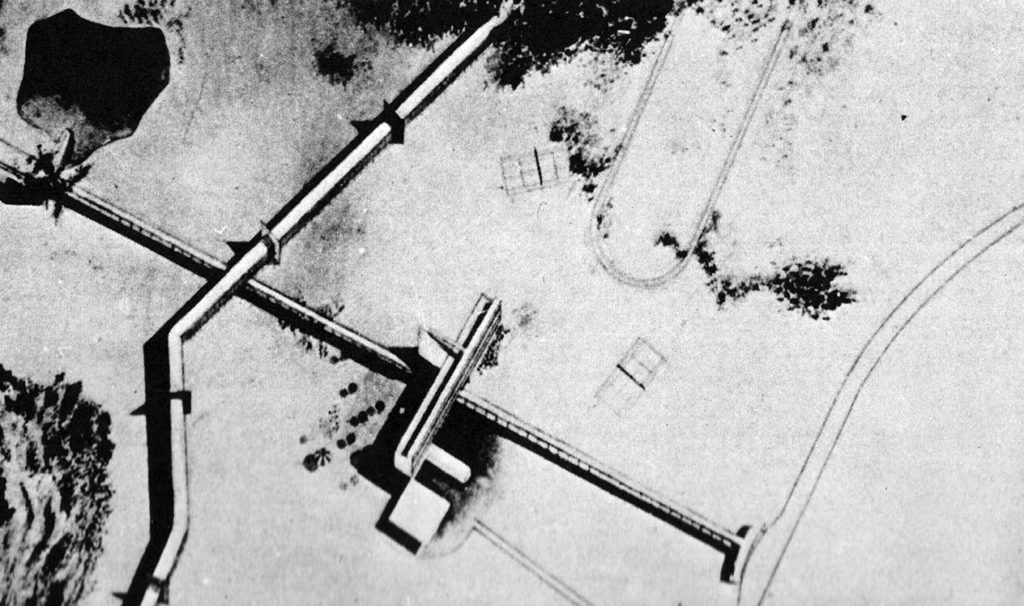

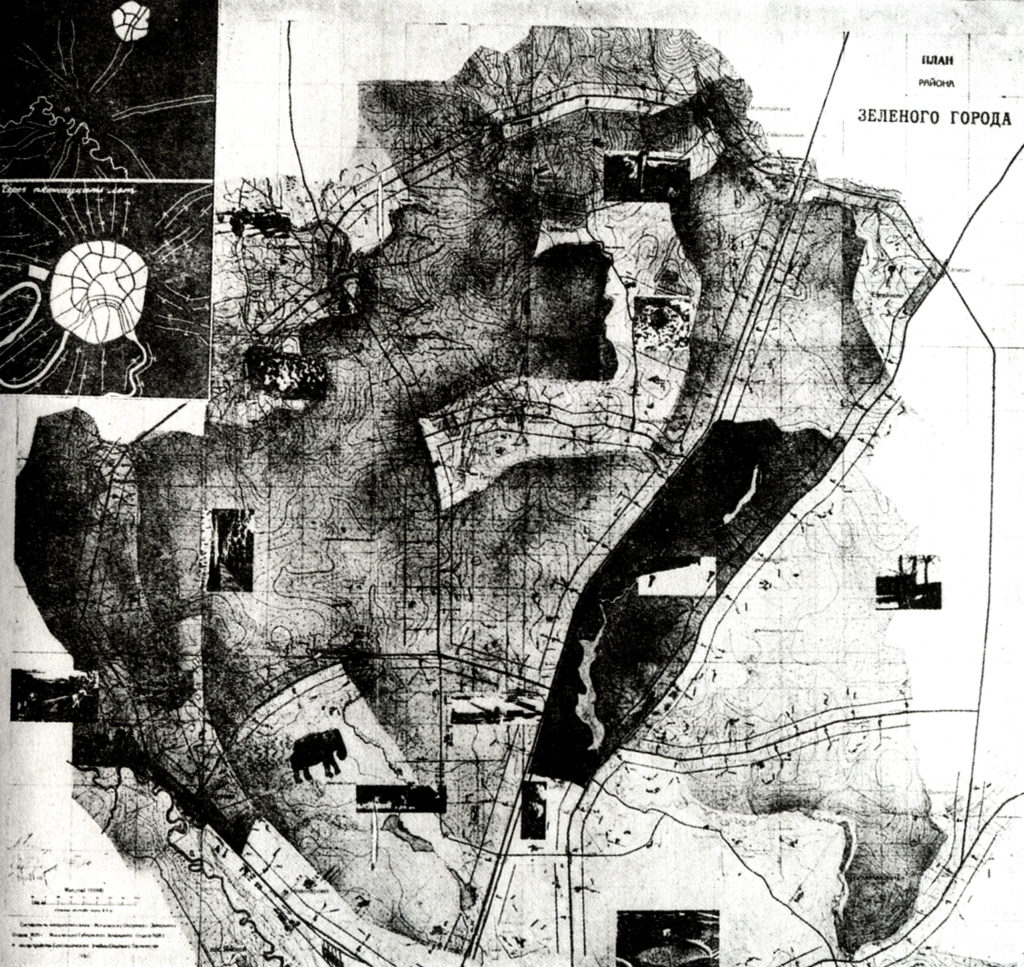

The supporters of disurbanism theorised the dispersion of the habitat across the territory, avoiding the density of the city, and using modular buildings distributed along infrastructural viability axes determined by the location of productive facilities. This development would be a consequence of the electrification of the country identified by Lenin as a pillar of the soviet revolution. The concept of disurbanism concept was initially propagandised by the sociologist Mikhail Okhitovitch, and Moisei Ginzburg , developing into one of the main themes of the last issues of SA magazine. In 1930, Ginzburg and Mikhail Barsch presented their radical “Green City” project for Moscow, proposing an immediate halt to new construction in the city, the transfer of public enterprises into external disurbanised locations, the transformation of the freed-up spaces into parks, and the dispersion of Moscow citizens along the roads linking the city with the rural population.

“When a man becomes sick, he can be cured with adequate medicines. It would however be more productive and less expensive to avoid illness manifesting itself. Just in this consists the socialist medicine: prophylaxis. When the city is ugly, when namely it is what it is, with all its attributes: noise, dust, lack of light, air sun, etc., we draw on medicines: homes and villas in the country, health resorts, rest homes, green cities. All this is medicine, a medicine which is necessary when a city exists, which we cannot avoid. But we cannot close our eyes in front of this double system of poison and antidote, which is the classical capitalist system of contradictions. This system must be contrasted by the socialist system of prophylaxis, the system of the elimination of the city, with all its specific attributes, promoting a settlement sodality of man able to solve the problems of work, of rest, of his culture, as a whole and uninterrupted process of socialist being.”

Traces of the disurbanist discourse can be found in the new City of Magnitogorsk, entirely planned by constructivist architects, and currently home to a population of 400,000 people. These visions also influenced the work of Nikolai Milyutin and his book Sotsgorod.